Revision of failed hip resurfacing arthroplasty to total hip arthroplasty-a case series and review of literature

2 El Bakey General Hospital, Ministry of Health, Cairo, Egypt, Email: btmnail2010@hotmail.com

Received: 01-Jun-2020 Accepted Date: Jul 06, 2020 ; Published: 13-Jul-2020

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Revision rate of hip resurfacing in most national registries nearly 3.5%. Conversion to total hip replacement may be the correct option for those whose activity levels changed and the need for hip resurfacing no longer required.

Purpose: Assessing outcomes of failed hip resurfacing to total hip arthroplasty. Primary outcomes included improvement of Oxford, WOMAC, Harris, and UCLA hip scores. Secondary outcomes included surgical site infection, residual groin pain, and heterotopic ossification.

Study design: Prospective case series.

Level of evidence: Level IV.

Patients and Methods: 25 patients underwent revision hip resurfacing to total hip arthroplasty. Mean age 56.8 years. Indications for revision: femoral neck fractures (10 cases), femoral neck thinning (3 cases), component loosening (4 cases) component dislocation (2 cases) persistent groin pain, and clicking (3 cases) and component wear (3 cases). Nineteen patients revised both components and six revised femoral components only.

Results: Average duration of follow up 26.8 months (28-48 months) and the procedure was successful in 23 (92%) patients. Preoperative Oxford, WOMAC, Harris, and UCLA hip scores were 21.3, 78.3, 35,7, and 2 respectively improved to 39.8, 11.1, 92.3, and 7 respectively at last follow-up representing statistically significant improvements (p<0.0001) for each score 3 cases (12%) with complications; surgical site infection (1 case), residual groin pain (1 case), and mild heterotopic ossification (1 case).

Conclusion: Conversion of hip resurfacing to THA has high satisfaction rates. These results compare favorably with those for revision total hip arthroplasty.

Keywords

hip resurfacing arthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty, femoral neck fractures, component loosening

Introduction

Hip resurfacing arthroplasty has become increasingly popular over the last decade [1]. The proposed advantages of that concept over total hip arthroplasty include femoral bone stock preservation, loading of the proximal femur in a physiologic manner so; less exposure to stress shielding effect, lacking femoral reaming or cementation minimize the risk of embolization, increase construct stability (due to the nearanatomical diameter of the articulating surface compared with the 28 mm or 32 mm Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) components) and improved proprioception of the hip joint with the ability of the patient to resume higher demand activities [2,3]. In addition; if conversion to total hip necessary; it would be relatively straightforward and less technically demanding. The previous advantages in addition to good clinical results of surface arthroplasty have led to an increasing number of joint replacements in younger active patients [4,5]. However; this age group faces an increased risk of early implant failure owing to their high activity level [6]. With the increasing number of primary THA procedures being performed and the decreasing age of patients undergoing the procedure, there is an inevitable associated increase in revision burden for arthroplasty surgeons.While early results of hip resurfacing have been promising, complications have been reported which require revision. These include femoral neck fractures [7] and recurrent pain and effusions thought to be related to an aseptic lymphocytic vasculitis associated lesion syndrome [8]. Large destructive lesions (pseudotumors) have also been reported which leads to soft tissue loss around the hip joint [9].

This prospective study evaluates the short-term and mid-term functional outcome of a case series of patients who underwent conversion of a hip resurfacing to a total hip replacement and reviews some of previous literature and studies concerning this issue.

Patients and Methods

The study initiated after receiving approval from the institutional ethics committee for research in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Also, written consent had been obtained from the patient for participating in the study.

Between May 2010 and December 2017, thirty-five patients with failed hip resurfacing arthroplasty were eligible to be a candidate for revision to total hip arthroplasty. Five patients died without completing the minimum follow-up period, three patients refused to participate in the study, and two patients lost completely during follow-up. Twenty-five patients (fifteen males) had been enrolled and continued in this study. Retrospective revision of enrolled cases medical records had been done through checking of the institutional registry. They were reviewed for indications for arthroplasty, comorbidities, concomitant procedures, cup size, femoral head size, and perioperative complications, including infection, dislocation, mechanical failure, and reoperation.

Mean age 56.8 years (41-69 years). Distribution of age shown in Table 1 average time to revision was 36.8 months (9-68 months). Indications for revision involved: femoral neck fractures 10 cases (40%), femoral neck thinning 3 cases (12%) (assessed as a reduction in the femoral neck of >10%) [10]. Also, component loosening 4 cases (16%), component dislocation two cases (8%) persistent pain and clicking 3 cases (12%), and severe wear of the components of resurfacing prosthesis 3 cases (12%). In all cases, laboratory investigations had been done to exclude infection. Demographic distribution of patients (Table 2).

| Age | Males | Females | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36-45 years | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 46-55 years | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Above 56 years | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| Total | 15 | 10 | 25 |

Table 1. Age distribution of patients

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 15 | 10 |

| Mean age | 63 Years | 54.7 years |

| Time to revision | 36.8 months | 42.1 months |

| Femral Neck fractures | 7 | 3 |

| Femoral neck thinning | 2 | 1 |

| Component loosening | 2 | 2 |

| Component dislocation | 2 | 0 |

| Groin pain | 2 | 1 |

| Component wear | 2 | 1 |

| Both component revision | 13 | 6 |

| Femoral component revision | 2 | 4 |

Table 2. Demographic distribution of patients

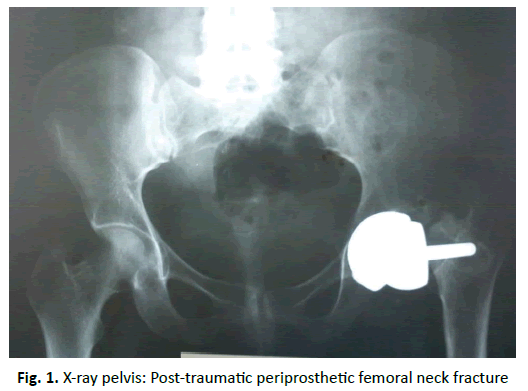

Radiographic evaluation through plain imaging studies included standard anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the pelvis and affected hip respectively done by two of the authors (Fig. 1). An examination is done for radiolucency, component loosening, femoral-neck narrowing, and heterotopic ossification as well as acetabular inclination and anteversion and femoral neck-shaft angle. Computed Tomography (CT) scans were obtained for all cases to assess the proposed component size, bone quality, and possible acetabular defects confirming their 3-dimensional extent and actual size.

Nineteen patients (76%) had a revision of both components while the remaining six (24%) underwent revision of the femoral component only (Table 3).

| Component revised | No. | FNF | FN thinning | Loosening | Dislocation | Pain | Wear | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both components | 19 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 19 |

| Femoral component | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Total | 25 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 25 |

| FN: Femoral Neck; FNF: Femoral Neck Fracture | ||||||||

Table 3. Distribution of revised component relative to revision indication

Templating was done for all cases to detect near the size of the implanted component, detecting any bone defect and possibilities of bone grafting. For Nineteen patients who had a revision of both components, acetabular cup 2 mm-4 mm larger than the extracted one was utilized and coupling metal on ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene used in seventeen cases while ceramic on a ceramic couple used in two cases. The average femoral head size of the femoral component implanted for females was 44 mm (39 mm-52 mm) and for males 49 (45 mm-58 mm). The average acetabular component extracted 50.9 mm (44 mm-60 mm) while the average implanted component 56.2 (53 mm-60 mm).

For cases of femoral component revision, a matching (to the retained acetabular component) modular cobalt chrome metal head fixed to an uncemented stem used in six cases. We were obliged to utilize head size-matched to the retained acetabular component ±.

Low molecular weight heparin (Enoxaparin) given twelve hours before surgery in a dose of 40 mg S.C. and started again 12 hours postoperative and then given daily until the patient was discharged from the hospital and continued for 35 days.

Pre-operative I.V antibiotic (1 gm 3rd generation cephalosporin) was administered to all patients. Preparation of two units of whole fresh blood to be ready for use according to intra-operative blood loss and preoperative patient hemoglobin level.

Surgical Procedure

In our study, the operative technique was tailored case by case. Epidural anesthesia used in 15 cases, spinal anesthesia in 4 patients, and general anesthesia utilized in 6 patients.

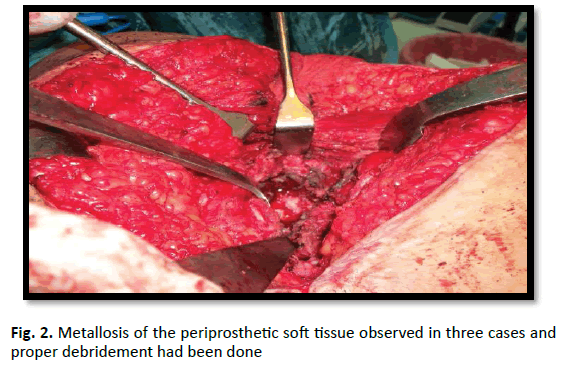

The posterior approach utilized in nine cases; the posterolateral approach used in eleven cases while the modified harding approach used in five cases. After skin incision; culture swabs of components, surrounding soft tissue, and samples of any effusions were taken for microbiological examination. Massive metallosis of the periprosthetic soft tissue observed in three cases and proper debridement had been done (Fig. 2).

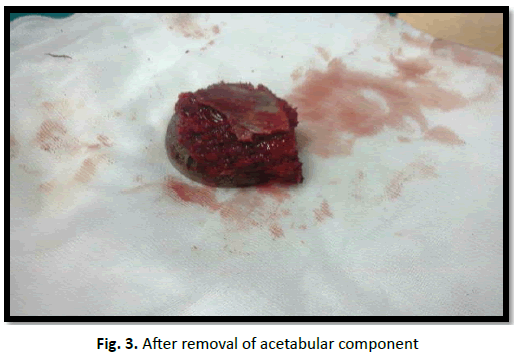

In cases where both components were revised the femoral neck osteotomy was performed (after dislocation of the joint) directly below the femoral component and the healthy bone from the femoral head and neck was used as an autograft for the acetabular or femoral reconstruction. The acetabular component was removed by the use of a fulcrum consisting of the trial acetabular liner and curved osteotome or cob elevator to allow relatively easy removal of the shell with minimal bone loss (Fig. 3). Any bone defect was dealt with either morselized autograft or femoral head allograft. Femoral preparation was done as for primary hip arthroplasty. A straight, tapered reamer was inserted into the femoral canal followed by incremental rasps as appropriate. Once the stem was firmly seated, a large diameter cobalt chrome head with a modular neck applied, and the reduction was performed. The suction drain was inserted deep to fascia lata followed by proper closure of the wound.

Postoperative I.V. antibiotic was administered (1 gram 3rd generation cephalosporin) and continued for 3 days. Patients revised without bone grafting were encouraged to mobilize by 2nd day postoperatively. The patient was trained to bear as much weight as he can bear with the aid of the walker for 3 weeks then using a cane for another 3 weeks then full weight-bearing without any aid. Those revised with bone grafting were encouraged for partial weight-bearing for the first six weeks.

First dressing after 48-72 hours according to the amount of blood drained. The average hospital stay was 5 days (4-10 days)

Follow-Up Regimen

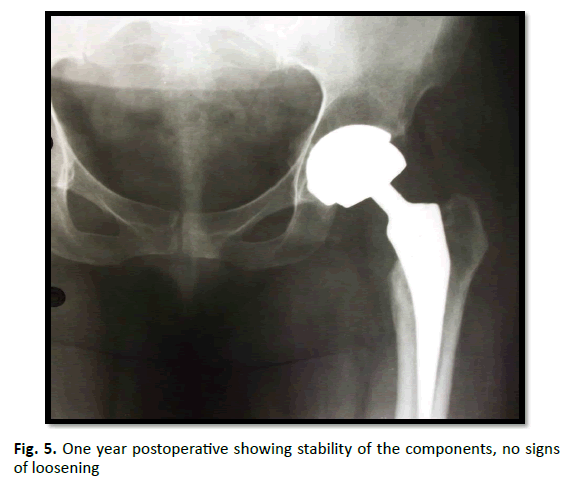

Patients were followed up clinically and radiologically at 3 weeks for 3 months and every 3 months for one year and periodically every 2 years with an average duration of follow-up 5 years (range, 4-10 years). Clinical follow-up through recording Oxford, Harris, WOMAC, and UCLA activity hip scores. Radiological assessment is done to determine the over-all alignment of the limb, the respective size, fit and positions of the prosthetic components relative to the bone, the presence of radiolucent lines in zones adjacent to the components, lytic lesions or spot welds at the bone prosthesis interface as well as trabeculae extending to the uncemented stem.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were expressed as frequency and percentages, and means with SD. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0.

Results

This prospective study conducted to evaluate the midterm functional outcome of case series of 25 patients who underwent conversion of a hip resurfacing to a total hip replacement. There was a male predominance (60% of the patients) in our study with a male to female ratio of 1.5:1. The mean age was 56.8 years (41-69 years). The study was an intermediateterm follow-up. The average duration of follow up was 26.8 months (28- 48 months). The procedure was successful and improvement of clinical outcomes with a reasonable amount of improvement included 23 (92%) patients. Evaluation parameters included Oxford, Harris and Western Ontario McMaster (WOMAC), UCLA activity hip scores, relief of pain, return to previous activities, and patient satisfaction. The study enrolled twenty-five patients (15 males).

Indications for revision in our study included femoral neck fractures 10 cases (40%), femoral neck thinning 3 cases (12%), component loosening 4 cases (16%) component dislocation 2 cases (8%), persistent pain and clicking 3 cases (12%) and severe wear of the components of resurfacing prosthesis 3 cases (12%). The average time to revision was 37.8 months (9-68 months). Cases with revision of both components, the average size of extracted acetabular component was 51.4 mm (44 mm-60 mm) relative to the revised component 55.7 mm (54 mm-60 mm) while the average femoral head size utilized for revision was 46 mm (38 mm-58 mm). Intraoperatively, a small amount of effusion observed in 2 cases which were blackish in color while in another 2 cases black staining of the pseudo capsule and periarticular soft tissues suggesting deposition of metallosis. The mean operative time of the patients was 55.4 ± 6.0 minutes. Mean blood loss was 400 ± 10.6 ml.

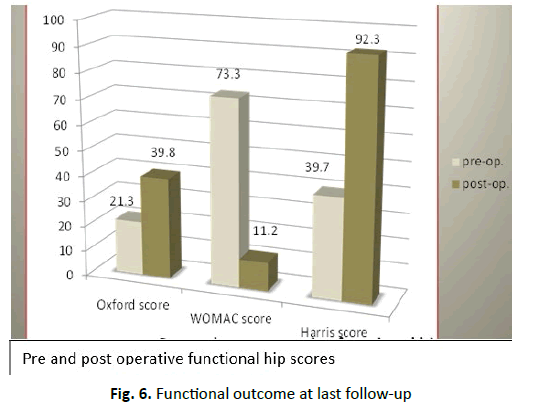

Clinical outcome assessed through average Oxford, WOMAC, Harris, and UCLA activity hip scores. Oxford hip score improved from 21.2 preoperatively to 39.8 postoperatively at last follow-up, WOMAC hip score improved from preoperative 73.7 to 11.1 at last follow-up visit while Harris hip score improved from 35.7 preoperatively to 92.3 at last visit of the patient with p<0.00001 in all parameters. The average UCLA activity score increased from 2 to 7 estimating the good satisfaction of the patient. No cases of neurological, vascular, or deep infection occurred. Distribution of outcome according to the indication of revision illustrated in Table 4.

| Indication No. |

Oxford score | Harris score | WOMAC score | UCLA score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | Postop | Preop | Postop | Preop | Postop | Preop | Postop | ||

| Femoral neck fracture | 10 | 22.8 | 39.5 | 26 | 98.8 | 92.5 | 7.4 | 2 | 9.3 |

| Femoral neck thinning | 3 | 18.9 | 38 | 31 | 96.5 | 91.8 | 11.2 | 2 | 8.5 |

| Loosening | 4 | 19.4 | 37.3 | 29 | 95.4 | 90.5 | 9.6 | 3 | 7.2 |

| Dislocation | 2 | 18.9 | 36.5 | 30 | 88.5 | 84.4 | 10.1 | 2 | 5.7 |

| Pain | 3 | 18.8 | 38.8 | 34 | 86.4 | 72.2 | 12.3 | 1 | 4 |

| Wear | 3 | 18 | 35.7 | 28 | 88.2 | 88.4 | 17 | 2 | 7.3 |

| Average | 21.2 | 39.8 | 35.7 | 92.3 | 73.3 | 7 | 2 | 7 | |

Table 4. Distribution of functional outcome according to indications

Complications

There were 3 cases (12%) in our study with complications. one case complicated by surgical site infection with serious drainage for more than seven days and was treated with oral antibiotics and daily sterile dressings until the wound closed completely. One case had residual groin pain, and the third case had mild heterotopic ossification. The later was treated by Indomethacin 25 mg oral capsule three times daily (total 75 mg) which continued for 4 weeks. Also, a physiotherapy program was encouraged to improve hip range of motion.

Discussion and Review of Literature

Revision rates of Hip Resurfacing Arthroplasty (HRA) have been reported to be higher than primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) and in most national registries accounts to be 3.5% over 15 years [11]. Revision of HRA is associated with a major risk of a 5-year re-revision of 11%, which is much higher than the 2.8% revision risk of a primary THA [12]. It seems logical as HRA mostly indicated in the younger age group who are characterized by a higher level of both daily and sports activities. This is in addition to the specific design of the prosthesis.

In our study, we aim at restoring the daily and sports activities of the patients for which they underwent their HRA surgery.

The most common indications for revision are femoral neck fracture (incidence range 0.9-1.1%) owing to osteoporosis or notching of the femoral neck during surgery [13,14], component loosening, infection, and metallosis with adverse local soft tissue reaction [6].

Other risk factors that may propose to HRA failure and the need for revision include age, gender and implant factors. Increased age accompanied by the poor bone quality which subjects the patient to complications as femoral neck fractures, osteoporosis of femoral neck, and aseptic loosening. Many studies emphasized that patients above 55 years had an increased risk of complications [6,15,16]. Female gender is a risk factor for implant failure, with revision rates in females significantly increased compared to males (5.7 vs 2.6%, p<0.001). Many studies have shown that the survival rate of HRA may reach 95% to 98% at 10 years in male patients [17]. The previous study’s factors are compatible with our study with some deviation owing to the small number of the series.

Implant factors that exaggerate risk challenges of revision include malposition which is associated with an increased incidence of aseptic loosening and increased metal ion release. This is due to the increased edge loading of the prosthesis and loss of fluid film lubrication [10]. Also; many studies have emphasized that decreased femoral component size is associated with increased release of metal ions with a subsequent incidence of failure for every 4 mm decrease in femoral component diameter [18].

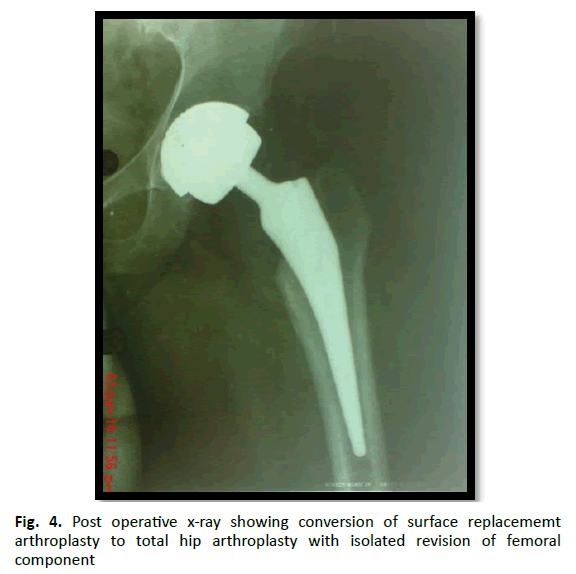

Component loosening in our study involved 4 patients. In 3 cases both components were loose and revised while in one case only the femoral component affected and isolated femoral revision with retention of the acetabular shell has been done (Fig. 4). The technique is less time consuming less technically demanding, minimizes the risk of dislocation owing to the use of large diameter femoral head and maintenance of residual acetabular bone stock [19]. The only drawback of this procedure concerned with conflicts about the use of metal on metal bearing surface total hip arthroplasty and corrosion-related complications. Recent studies utilized the femoral component with dual mobility femoral head through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved the use of that [20,21].

Sandiford et al. [22] declared that complete revision of both acetabular and femoral components to a THA would minimize the potential sources of cobalt and chromium ions and consequently could produce good short-term clinical outcomes.

In the setting of metallosis which explored intraoperatively in 3 cases, a proper understanding of the characteristics and anatomic relationships is essential as this soft tissue contamination can distort normal surgical landmarks. Thorough debridement of metal debris and inflammatory soft tissue was performed. Any cystic or lytic osseous lesions were packed with bone graft. Extensive osteolysis may require the use of bone grafting along with supplemental fixation. Patients with these presentations had been revised by ceramic on a ceramic bearing couple with functional outcomes similar to those of Willert et al. [23].

Advantages of conversion of hip resurfacing to THA include avoidance of implant mismatch awareness, elimination of cobalt or chromium ions source if titanium-alloy femoral and acetabular components, or ceramic femoral heads are utilized [9]. However; some shortcomings may limit the prevalence of this strategy namely minimizing bone stock owing to bone loss on the removal of hip resurfacing implants and concern of stability due to the use of the smaller femoral head in THA compared with that of hip resurfacing implants [24].

The targets to be achieved in this study are the relief of pain and returning to patients’ daily and sports activities. In the last follow-up, all patients (except one) returned back to their daily activities and sports. One patient has a moderate reduction in the range of motion owing to heterotopic ossification.

Clinical outcomes of conversion of HRA to total hip arthroplasty had been assessed via some studies. Su et al. [7] declared that clinical outcomes of this conversion were related to the indication of revision and the highest postoperative outcome observed in patients who underwent conversion for femoral neck fracture or implant loosening (Fig. 5). The worst outcomes were seen in patients who underwent a revision for unexplained pain or metal sensitivity.

In our study the average highest outcome according to Oxford, Harris, WOMAC, and UCLA activity hip scores observed in patients revised for femoral neck fractures with values at last visit of 39.5, 98,8, 7.4, and 9.3 respectively. The worst outcome observed in cases revised for unexplained pain with values of 38.0, 38.6, 4, 12.3, and 4 respectively. Our study outcome is comparable with many studies as Su et al. [7].

Revision of a single component of HRA, with retention of the remaining components, has been associated with mixed clinical results. In a study comparing 21 patients undergoing conversion of HRA to THA to patients undergoing primary THA, found that in the 18 patients who underwent femoral-sided revision only there was no clinical difference at a mean 46-month follow-up with regard to the mean Harris hip score; WOMAC and UCLA activity score [25]. The results could not be compared with those of our study as we have no comparative cohorts of primary THA (a limitation in our study) (Fig. 6).

Many studies emphasized that on revising resurfacing hip arthroplasty due to causes related to femoral component, the decision to change the femoral component only or both femoral and acetabular depends largely on the orientation of the acetabular component [12,18].

In our study, we followed a similar strategy that if the lateral acetabular opening angle was greater than sixty degrees, we changed both acetabular and femoral components because some vertical orientation of the cup may be compatible with a femoral component in resurfacing arthroplasty but this position is difficult to be compatible with a fixed angle of the stemmed metal on metal THA prosthesis and lateral subluxation mostly occur.

On the other hand; cases with a lateral acetabular opening angle of resurfacing prosthesis near forty degrees so during revision the fixed angle of the stemmed metal femoral component usually becomes compatible with the previous metal acetabular cup so in these cases we revised only femoral component.

Revision of both acetabular and femoral components of HRA to THA has varying clinical outcomes reported across multiple studies [8]. A registry study of 882 HRA revision emphasized that no difference in re-revision rates and clinical outcomes between the acetabular-sided, femoral-sided, or combined acetabular and femoral-sided cohorts [26]. This finding correlated with the results of the prior study by Su et al. [7]. Similar findings have been illustrated in our study (Table 5) with no marked differences in clinical outcome between both component revision and isolated femoral component revision regarding Oxford, Harris, WOMAC, and UCLA activity hip scores. A small difference in outcome noticed in our study regarding the indication for revision with the worst outcome in patients revised for component loosening, unexplained pain, and component wear (Table 5).

| Score | Revised component | FNF | FN thining | Loosening | Dislocation | Pain | Wear | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication of révision | ||||||||

| Oxford hip score | Both components revision | 38.8 | 37.1 | 35.8 | 35.1 | 37.8 | 34.7 | 36.5 |

| Femoral revision | 39.3 | 37.8 | 35.8 | 36 | 38.7 | 35.1 | 37.3 | |

| Harris hip score | Both components revision | 96.8 | 95 | 94.6 | 86.2 | 84.3 | 87 | 90.7 |

| Femoral revision | 98 | 96.2 | 95 | 88.4 | 85 | 88.7 | 91.9 | |

| WOMAC score | Both components revision | 7.8 | 12 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 11.8 | 12.6 | 10.55 |

| Femoral revision | 17 | 10 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 14.5 | 12.35 | |

| UCLA activity score | Both components revision | 8.1 | 7.8 | 7 | 5 | 6.4 | 7 | 6.9 |

| Femoral revision | 9.2 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 8.1 | 6.21 |

Table 5. Functional outcome relative to indication of revision and revised component

Sandiford et al. [22] in a review of 25 patients undergoing conversion of surface arthroplasty to THA, found significant postoperative increases in Oxford, Harris, and WOMAC hip scores, with clinical results similar to revision THA.

Reports on clinical outcomes following HRA revision for complications associated with metal wear are mixed, with some studies touting midterm clinical success rates as high as 97%, while other data shows that revision for implant wear is associated with a significantly worse outcome when compared with revision for mechanical etiologies [7,21]. These reports outcomes support our results regarding worse outcomes of revised cases for implant wear relative to those of femoral neck fractures (10 cases) or femoral neck thinning (3 cases) (Table 5).

Limitations of The Study

Our study presents some limitations, a namely small number of patients, the follow-up period is somewhat short relatively, and lacking comparative study. The technique itself has some limitations owing to the concerns of metal on metal coupling in hip arthroplasty. Furthermore, a systematic approach to the revision of hip resurfacing arthroplasty to total hip arthroplasty is necessary to ensure optimal clinical results.

Conclusion

There is a clear universal consensus that clinical outcome of conversion of HRA to THA is dependent on indication for revision, with revision for mechanical etiologies exhibiting better results than revision for complications associated with metal wear or component loosening. Our study supported by many literature reviews refer to the preference of this approach of conversion as it can avoid implant mismatch awareness, eliminate and minimize cobalt or chromium ion source if titanium alloy or ceramic components utilized. However; decrease bone stock owing to bone loss on the removal of resurfacing implants and concern of stability due to the use of smaller femoral head break the progress of this syllabus. Further systemic reviews work, randomized controlled studies and research of high levels of evidence are needed to facilitate the progress of this technique. It is also logical to assume that as the number of resurfacings increases, so will the number of revisions. This will provide a larger series for study and also provide data based on component design.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest in the manuscript, including financial, consultant, institutional, and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest. The authors had no disclose for any financial ties to the subject of this research.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study according to the rules of the hospital research ethical committee.

All procedures performed in our study were under the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

REFERENCES

- Amstutz H.C., Le Duff M.J., Campbell P.A.: Clinical and radiographic results of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing with a minimum ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2663-2671.

- Klein G.R., Levine B.R., Hozack W.J., et al.: Return to athletic activity after total hip arthroplasty. Consensus guidelines based on a survey of the Hip Society and American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:171-175.

- McKee G.K., Watson-Farrar J.: Replacement of arthritic hips by the McKee-Farrar prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1966;48:245-259.

- Barrack R.L., Ruh E.L., Berend ME.: Active patients perceive advantages after surface replacement compared to cementless total hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3803-3813.

- Lavigne M., Masse V., Girard J., et al.: Return to sport after hip resurfacing or total hip arthroplasty: a randomized study. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2008;94:361-367.

- Carrothers A.D., Gilbert R.E., Jaiswal A., et al.: Birmingham hip resurfacing: the prevalence of failure. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1344-1350.

- Su E.P., Su SL.: Surface replacement conversion: results depend upon reason for revision. J Bone Joint. 2013;95:88-91.

- Shimmin A.J., Bare J., Back D.L.: Complications associated with hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2005;36:187-193.

- Glyn-Jones S., Pandit H., Kwon Y.M., et al.: Risk factors for inflammatory pseudotumour formation following hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1566-1574.

- Jolley M.N., Salvati E.A., Brown G.C.: Early results and complications of surface replacement of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:366-377.

- Australian orthopaedic association. National joint replacement registry Annual report. Adelaide: AOA. 20010:20-44.

- Buergi M.L., Walter W.L.: Hip resurfacing arthroplasty: The Australian experience. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:61-65.

- Anglin C., Masri B.A., Tonetti J., et al.: Hip resurfacing femoral neck fracture influenced by valgus placement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465:71-79.

- De Haan R., Campbell P.A., Su E.P., et al.: Revision of metal-on-metal resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: the influence of malpositioning of the components. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1158-1163.

- Gross T.P., Liu F.: Risk factor analysis for early femoral failure in metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: the effect of bone density and body mass index. J. Orthop Surg Res. 2012;7:1.

- Prosser G.H., Yates P.J., Wood D.J., et al.: Outcome of primary resurfacing hip replacement: evaluation of risk factors for early revision. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:66-71.

- Murray D.W., Gundle R., Gill H.S., et al.: The ten-year survival of the Birmingham hip resurfacing: an independent series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;949:1180-1186.

- Langton D.J., Jameson S.S., Joyce T.J., et al.: The effect of component size and orientation on the concentrations of metal ions after resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1143-1151.

- Langton D.J., Jameson S.S., Joyce T.J., et al.: Poor outcome of revised resurfacing hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2010;81:72-76.

- Blevins J.L., Shen T.S., Morgenstern R.: Conversion of hip resurfacing with retention of monoblock acetabular shell using dual-mobility components . J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2037-2044.

- Pritchett J.W.: One-component revision of failed hip resurfacing from adverse reaction to metal wear debris. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29:219-224.

- Sandiford N.A., Muirhead-Allwood S.K., Skinner J.A.: Revision of failed hip resurfacing to total hip arthroplasty rapidly relieves pain and improves function in the early post operative period. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:88.

- Willert H.G., Buchhorn G.H., Fayyazi A., et al.: Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints. A clinical and histomorphological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:28-36.

- Loughead J.M.., Starks I., Chesney D., et al.: Removal of acetabular bone in resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: a comparison with hybrid total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:31-34.

- Ball S.T., Le Duff M., Amstutz H.C.: Early results of conversion of a failed femoral component in hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:737-741.

- Marshall D.A. et al.: Hip resurfacing versus total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review comparing standardized outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2014;472:2217-2230.

Journal of Orthopaedics Trauma Surgery and Related Research a publication of Polish Society, is a peer-reviewed online journal with quaterly print on demand compilation of issues published.

Journal of Orthopaedics Trauma Surgery and Related Research a publication of Polish Society, is a peer-reviewed online journal with quaterly print on demand compilation of issues published.